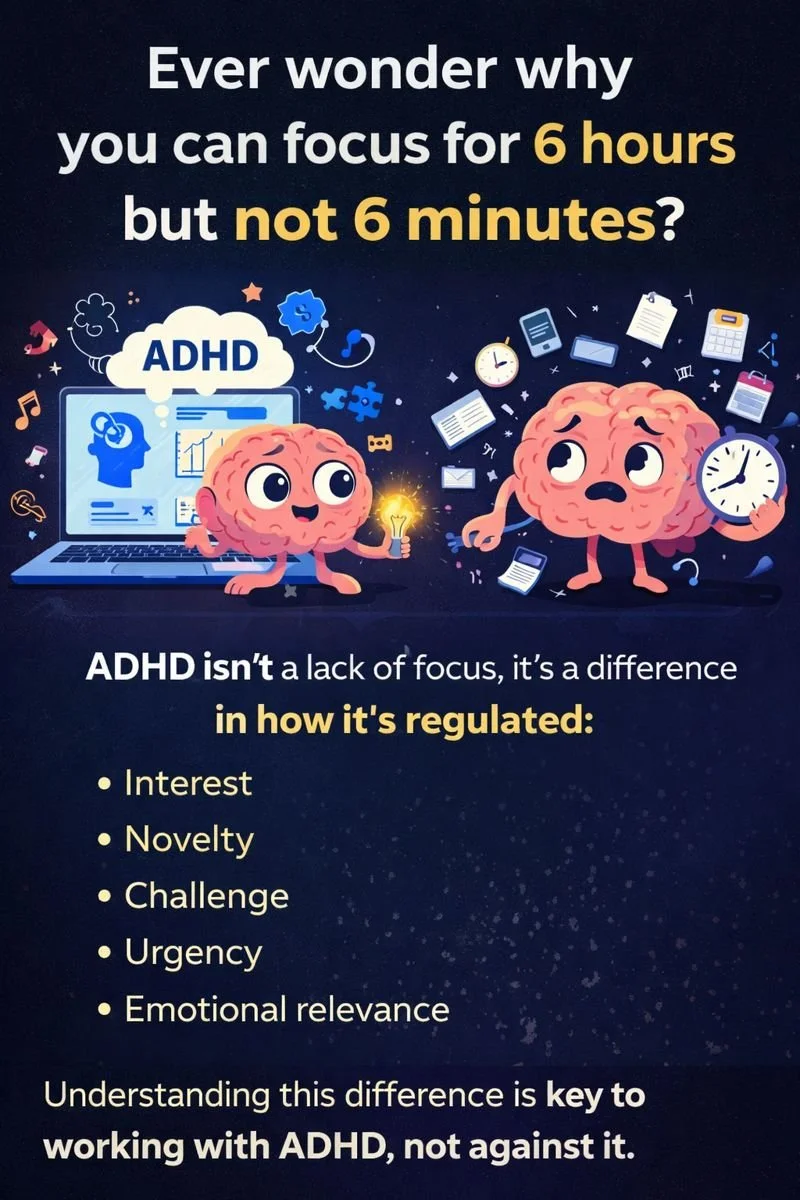

You’re Not Lazy: Why Focus Works Differently in ADHD

Why you can focus for 6 hours on one thing—and not 6 minutes on another

If you have ADHD, you’ve probably heard some version of this before:

"If you can focus on that, you could focus on anything if you really tried."

ADHD isn’t a lack of focus.

It’s a difference in how focus is regulated. Understanding this difference—rather than judging it—can fundamentally change how you work, learn, train, and live.

ADHD Is an Interest-Based Nervous System

Most people are taught that motivation follows importance:

Do what matters first.

ADHD doesn’t work that way. ADHD is best understood as an interest-based nervous system, not a priority-based one. Attention is more reliably activated by:

Interest

Novelty

Challenge

Urgency

Emotional relevance

This is why someone with ADHD might:

Hyperfocus for hours on a project, game, or topic they care about

Struggle to start or sustain attention on tasks that feel boring, repetitive, or low-reward—even when those tasks are important

This isn’t laziness or defiance. It’s neurobiology.

The Role of Dopamine: Motivation Comes Before Action

To understand why interest matters so much, we need to talk about dopamine.

Dopamine is often called the “reward chemical,” but it’s more accurate to think of it as the motivation and engagement neurotransmitter.

In ADHD:

Dopamine signaling tends to be lower or less consistent in key brain networks

This makes it harder to initiate tasks that don’t offer immediate stimulation or payoff

Once interest or urgency kicks in, focus can lock in intensely (hyperfocus)

This explains why ADHD brains often respond well to:

Novelty (something new or different)

Urgency (deadlines, pressure, competition)

Immediate feedback or rewards

External structure rather than internal willpower

The brain isn’t refusing to cooperate—it’s waiting for enough stimulation to engage.

Why “Just Try Harder” (and Shame) Makes It Worse

When ADHD is misunderstood, people internalize messages like:

“I’m lazy”

“I should be able to do this”

“Something is wrong with me”

Shame increases stress, and stress further impairs:

Executive functioning

Emotional regulation

Working memory

Task initiation

In other words, shame activates the very conditions that make ADHD symptoms worse. Research consistently shows that self-criticism does not improve motivation in ADHD. Compassion, understanding, and appropriate supports do.

Working With an ADHD Brain (Not Against It)

When you understand how ADHD actually works, strategies shift from forcing compliance to designing environments that support engagement:

Externalizing structure (timers, reminders, visual cues)

Breaking tasks into dopamine-accessible steps

Pairing boring tasks with stimulation

Using values, meaning, and interest to guide effort

Reducing shame and increasing curiosity

The goal isn’t to “fix” the brain.

It’s to build systems that fit the brain you have.

Understanding Your Brain Changes How You Work With It

ADHD is not a character flaw.

It’s not a lack of discipline.

And it’s not a failure of effort.

It’s a different operating system—one that can be incredibly creative, focused, and effective when understood and supported.

When you understand your brain, you stop fighting it—and start working with it